Published September 1st, 2013

Description:

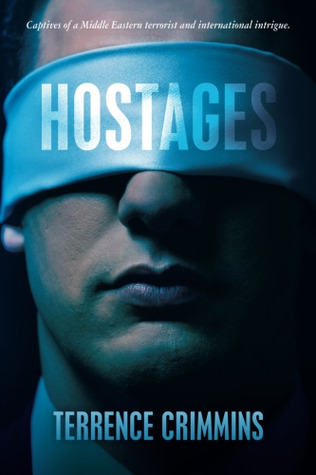

A young man who has just graduated from Georgetown is finishing up his part time job delivering pizza and ends up in the wrong place at the wrong time and is taken hostage by a Middle Eastern terrorist. After he survives this adventure he goes on a media tour around the country with another former hostage, amidst lingering international intrigue.

GUEST POST

What does the Media do?

I sometimes think that there are a lot of times when someone does something just to get the attention of the media, because they want to be famous, like when someone claims that they have the winning lottery ticket that they never really bought. But other examples can cause a lot more trouble, as when someone holds people hostage, or kidnaps someone, committing a crime they know they'll never get away with, and their main motive is to get into the spotlight for as long as they can. There are plenty of people in jail for stuff like that, but the problem is that their actions hurt the lives of other people, often resulting in death.

It makes you wonder about what the bad side of publicity is. After all, would those events occur if people weren't going to be made famous by them? Probably not. I suppose that doesn't mean that we shouldn't have newspapers and news teams and all, but shouldn't there be a limit? Princess Diana being chased around by all those Paparazzi certainly thought so, God rest her soul.

What interests me is what Tom Wolfe calls the ricochet effect of journalism. He means that someone does something purely to get the attention of the media, and that this action ricochets into the lives of many people in ways that could not have been predicted. This kind of situation seems to me to be very interesting to explore.

My novel, Hostages, seeks to explore this question, to some degree, and looks at the motives of a man who takes Americans hostage, which results in enormous inconveniences for many, many people.

What do you think about the dangers of the media?

Thank you, Mr. Terrence Crimmins

EXCERPT:

Excerpt:

This was the moment André had been looking forward to for many years.

André Armoceeda had grown up in Lebanon and was not unaccustomed to chaos. He reveled in anarchy in fact, and a history of past successes in that dramatic part of the world had helped to place him on that balcony, flanked by two steely-eyed Iranian stalwarts. The Iranians were standing at attention and they too had Uzis, which were clutched upright with the barrels in front of their noses. André’s gun moved casually about as he spoke, as though he might like to shoot a few bystanders for the fun of it.

André had been born a Christian in Beirut in 1948, in what was then a rising metropolis by Western standards. It was fast becoming a playground for the rich, or a place for the display of western vices, depending on your point of view. His father was for a time fortunate in economic matters. As a young entrepreneur in what was then a tourist Mecca, he owned three hotels before they were demolished by Moslems in 1964; at this time André was kidnapped by the occupying vandals and taken away to Syria. He never learned what had happened to his parents, which was probably for the best. They'd been gunned down on their knees while his father's flagship hotel was burning down.

André was taken to the western part of Syria, which had just been cleansed of the Christians and their large private farming enterprises. Here he had a change in vocation. Instead of head bellboy he became latrine cleaner, then pig tender, wheat planter and gradually supervisor as he worked his way up the ladder. And the Syrians were impressed. Here was evidence of the advance of Allah, where a young man who was formerly a tool of the barbarians was rapidly becoming a soldier in the army of His justice. (And his last name was changed to Abdul, a far more fitting name for a soldier in the army of Islamic Justice.)

But André was drawing further into himself, which might be expected under such a difficult transition. He was, like his father, a strong willed man; but also, like his father, he was accustomed to adapt to circumstances.

And so it was not to help Allah when André joined the Syrian Army when he turned 18, but to obtain a higher form of servitude. Gradually rising through the ranks before an Israeli bullet removed the two small fingers of his left hand during the war of 1967, André Abdul had become a hero.

But he did not consider himself a hero, for he thought that the Syrians were cowards. They'd lost battles where they'd outnumbered the Israelis three to one. The Syrian infantry, formerly accustomed to bare feet, had on several occasions slashed off their boot strings with razors so that they might retreat more in a manner to which they were accustomed. Cowards! And as they were fleeing, the Israelis were firing on them with the same Russian tanks they'd just abandoned. Cut off your boots, get shot with your own weapons, and you call yourself soldiers?

But it was only in his own soul that André reminisced in this manner, for his main goal was to insulate himself from what he'd come to consider a world full of fools. So there was a basic irony in his character during his advance in the Syrian armed forces. The promotion to lieutenant colonel and the purchase of a house in Damascus did not satisfy him, as might be expected of one who had been diverted from upper class to serfdom. Andre wanted and expected to feel himself a part of the ruling class again.

So he resigned his position in 1982, and went back to Beirut, this time with the other team, as it were.

Here André was again successful. His brash demeanor and military connections stood him well in this chaotic environment, and even attained him the adoration of Iran's Party of God, as well as certain of the Ayatollah's chieftains. They considered him a great asset in their undeniable goal: the humiliation of spoiled and sinful Western decadence by the mighty hand of Allah.

His leadership and charisma were very noticeable in helping them gain a strong foothold on the Moslem side of the Green Line in East Beirut, where André Abdul was able to open a Swiss bank account with profits from the heavy arms trade there. Eventually, as his presence in Beirut became more well known, the financiers of Islam grew to respect him enough to let him plan and lead this essential mission.

So André was quite satisfied by the view that day from the balcony, the yellow POLICE LINE DO NOT CROSS tape, the jeeps, the silent soldiers, and most of all, the cameras. He smiled benignly at these signs of crisis in the Western world of fools.

And he rose to the occasion for propaganda which might even increase his stature in that other Middle Eastern world of fools. The tools were certainly at his command. Hostages. A worldwide audience. Washington, DC, the center of power. But most of all he appreciated that last minute gift of fortune, that perfect vehicle of propaganda, the Pizza Boy.

“We have inside this building twenty hostages who shall not be released until our demands are met. I will not state these conditions now, but shall give them to you in writing through an intermediary.

“Now I would like to speak to you about the intermediary. He is an American citizen who was delivering pizza to the spies who work here; yes spies, do not bother to deny it. He is one of your own kind American people, a hard working individual who is crushed under the merciless heel of your capitalist pigs. How could we be more honest than through negotiations with one of your own downtrodden? Allow me to show him to you.”

Tom was inside the glass doors trembling during this little speech. His captors had re-costumed him for the presentation, replacing his ban lon shirt with a ribbed undershirt, his cotton blend slacks with a pair of sweat pants, and his penny loafers with a pair of Converse Sneakers which, unfortunately, were a size too small.

It was difficult for Tom as he was pushed roughly through the doorway by Allah’s servants in the tight and unfamiliar sneakers. But André was in his glory, rising far above this world of the mediocre. He raised Tom up to a firmer stance. There he stood, eyes squinting at the camera lights, his hands clad in plastic handcuffs, slightly chilled by the spring breeze on his new attire, as André introduced him.

“Here you are America, take a look at your Pizza boy.”

About the author:

I grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as the youngest of nine children, eight boys and one girl. The thing we lived by was Irish Catholic sarcasm, in a family that always found a joke to circumvent any upcoming tension. A student at Catholic schools just after they stopped corporal punishment, I learned in the old fashioned methods that did not involve group work or student centered classrooms. My greatest achievement in grade school might have been writing the class play in sixth grade, based on Around the World in Eighty Days, by Jules Verne. I enjoyed high school, though I was kicked out of the honors classes when I spent all my time campaigning for George McGovern to beat Richard Nixon. The other change that I made was quitting sports, football, diving and baseball, to be in plays, which was a fortunate decision, including meeting a lot more girls. I skipped my senior year to go to Boston College, a fine Jesuit school.

There I learned how to drink beer, play rugby and read 600 page history books in small print. I really enjoyed the academics of college, and professors inspired me. They seemed to be on another level of consciousness, and I really enjoyed history and philosophy classes, which were my double major. I wrote a senior thesis about the legacy of Walt Whitman, based on two semesters of independent study with my mentor, Alan Lawson. Near graduation he cautioned me on the tale of the sorcerer's apprentice, and the image of the Disney cartoon with Mickey Mouse flying around the sorcerer's chamber screwing things up came to haunt me. In time, it seemed, that I was more the artist than the straight and organized academic with the blue blazer, grey slacks, oxford shirt and red and grey striped tie. On another front I took a class in Soviet Philosophy and wrote a paper making fun of my being in the class, having myself as a man who'd been kicked out of the Federal Writer's Project for not cracking down on the Communists and sent to England for a seminar on Soviet Philosophy led by Nikolai Nastuschen, who was a model of the professor, the late Peter Blakely. At that time he was one of the editors of Studies in Soviet Thought, where he published my paper.

On graduation, when I wanted to do graduate work, the professors counseled me that I'd done a lot quickly, and that I should take a break for a while. So I became a bohemian. Back in the sixties, people used to talk about not selling out and leading the life as an artist, but if you actually did it they thought you were a lunatic. Well, I was that lunatic. I worked in restaurants for ten years, waiting on tables and tending bar. There I met a lot of people from other countries, some of whom were the inspiration for characters in my novels. I worked for a time in a restaurant that was managed by a man who was a veteran of the Special Forces of the Israeli Army, and a restaurant down the block was Middle Eastern, and owned by people from Lebanon. Later I worked in a restaurant that had waiters who were natives of Chile, and I learned a lot about that country. These were very interesting people, and I'm grateful that I met them.

In time I took up another profession that allowed time for reading, and that was driving a cab. It was great, if you liked to read, and I did, where I got to explore all kinds of fiction and biographies. I also met a lot of interesting people. The majority of people who take cabs are the very poor and the moderately wealthy. The very rich have limos, and the rest of us drive cars. I drove a lot of poor people who rode at government expense, and it was interesting getting a take on that. Most of these were medical fares, or from an emergency medical center where people were taken when they were found in the dark of night with delirium tremens, etc. I also drove a lot of veterans, mostly from World War II, on medical fares, and they were very interesting to talk to. Eventually I was doing a lot of Kosher Food deliveries, and got so much that I didn't have to lease a cab anymore and did well using my own car. But I had to get a real job eventually, so I went back to Boston College to get a Masters degree to become a teacher.

I really found it interesting to go back to my alma mater and see the changes that had taken place in the history department. Most of the major domos I had studied under previously were being put out to pasture, and there were new professors running the show. I revisited my thesis about Whitman, and did two more semesters of independent study with new professors, and studied pedagogical movements that started to answer the challenge that Whitman put to America in his essay Democratic Vistas, where he posited that American might be a materialistic bonanza but a cultural disaster if there were not a democratic cultural revolution to accompany the political one. Once again I enjoyed my time in academia, though, a little older, I wasn't distracted by keg parties and rugby games. (I had moved on to camping trips and fly fishing in New Hampshire and Vermont.)

Since that degree I've been teaching in Baltimore for seven years, which is a bit of a trip, to say the least. It has been quite interesting to see this unique American sub-culture, where they are many interesting characters.

Website / Blog ** Facebook ** Twitter

3 comments:

Cartea pare interesanta iar coperta ii da un aer misterios.

Nice, really nice! Great cover, great description and great guest post!

Thank you kindly.

Another thing that interests me is the perspective of foreign nationalis in the United States, and their view of what they see....

Post a Comment