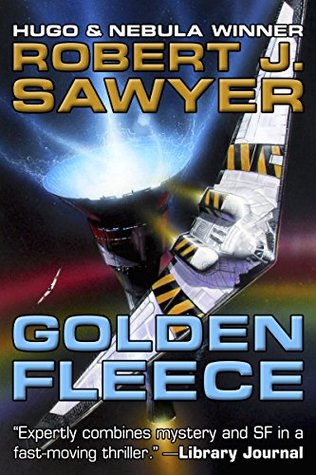

Golden Fleece

End of an Era

End of an Era

Starplex

Frameshift

Golden Fleece

Winner of the Aurora Award for best novel of the year. Named best novel of the year by The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

MURDER IN SPACE

Starcology Argo. A superstarship on a mission to a distant world. Controlled by a monumental computer named JASON, the Argo proceeds flawlessly . . . until death strikes its sleek decks with sudden and mysterious precision.

Astrophysicist Diana Chandler is dead of radiation. Her body lies in the Argo's ramfield — where hydrogen ions are funneled into the engines. Chandler's death has been deemed suicide. But her ex-husband, Aaron Rossman, isn't so sure. As he probes further, he becomes certain that Diana's death is a matter of murder — and that the murderer is JASON!

Now Rossman must face the unthinkable: why would an artificial intelligence conceive and execute that most heinous of human crimes? And if so, can a mortal mind take on a cunning computer . . . and survive?

Paleontologist Brandon Thackeray is eager to find out what killed the dinosaurs. With a newly developed, still-experimental timeship, he will be able to do what no human being has ever done: stand face-to-face with a living, breathing dinosaur. But he and his partner (and rival) Miles "Klicks" Jordan discover that they are not the only intelligent creatures on Earth at the end of the Cretaceous. There's a war going on and the dinosaurs are right in the middle of it.

Please note that this book is not part of The Quintaglio Ascension Trilogy. It is a stand-alone novel set on Earth.

The only novel of its year to be nominated for both the Hugo and Nebula Awards. Starplex won Canada's Aurora Award for best novel of the year.

For nearly twenty years Earth's space exploration had exploded outward, thanks to a series of mysterious, artificial wormholes. No one knows who created these interstellar passages, yet they have brought the far reaches of space immediately close. For Starplex Director Keith Lansing, too close.

Discovery is superseding understanding. And when an unknown vessel — with no windows, no seams, and no visible means of propulsion — arrives through a new wormhole, an already battle-scarred Starplex could be the starting point of a new interstellar war . . .

Frameshift won Japan's Seiun Award and was a finalist for the Hugo Award.

Pierre Tardivel is a scientist working on the Human Genome Project with the Nobel Prize winner, Dr. Burian Klimus. A driven man, Pierre works with the awareness that he may not have long to live: he has a fifty-fifty chance of dying from Huntington's disease, an incurable hereditary disorder of the central nervous system. While he still has his health, Pierre and his wife decide to have a child, and they search for a sperm donor. When Pierre informs Dr. Klimus of their plan, Klimus makes an odd but generous offer: to be the sperm donor as well as to pay for the expensive in vitro fertilization. Shortly thereafter it transpires that Klimus might be hiding a grim past: he may be Ivan Marchenko, the notorious Treblinka death-camp guard known as Ivan the Terrible.

While digging into Klimus's past with the help of Nazi hunter Avi Meyer, Pierre and his wife discover that Pierre's insurance company has been illegally screening clients for genetic defects. The two lines of investigation begin to coverage in a sinister manner, while they worry about the possibility of bearing the child of an evil, sadistic killer . . .

In 2007, a signal is detected coming from the Alpha Centauri system. Mysterious, unintelligible data streams in for ten years. Heather Davis a professor in the University of Toronto psychology department, has devoted her career to deciphering the message. Her estranged husband, Kyle, is working on the development of artificial intelligence systems and new computer technology utilizing quantum effects to produce a near-infinite number of calculations simultaneously.

When Heather achieves a breakthrough, the message reveals a startling new technology that rips the barriers of space and time, holding the promise of a new stage of human evolution. In concert with Kyle's discoveries of the nature of consciousness, the key to limitless exploration — or the end of the human race — appears close at hand.

This edition includes a reading group guide.

Read an excerpt HERE!

AUTHOR's Q&A

1. Did you intend the character of Jason (the computer in Golden Fleece) as a tribute to HAL 9000?

Oh, absolutely. I saw 2001 in the theatre when it first came out in 1968, when I was eight years old. I was fascinated by the character of HAL. But there never really was a good explanation for why HAL did the things he did; that he’d been lied to or given conflicting instructions wasn’t enough, I thought. I wanted to try something really challenging – to write believably from a computer’s point of view, and to give it believable, psychologically plausible motivations. So, yes, Jason is a tribute to HAL, but also my attempt to grapple with the issues surrounding HAL that frustrated me.

2. In Factoring Humanity, you seem optimistic about artificial Intelligence and its scientific prospect, but worried about its ethics effects. Looking back at it now, how do you regard it? Do we need or can we lock the AI genie back into the bottle?

Well, I’d say the exact opposite: in Factoring Humanity, I was pessimistic about artificial intelligence – in fact, it’s probably my most pessimistic take on the topic in a career that’s being dealing with AI from the very beginning, starting with my first novel, Golden Fleece, in 1990. My more recent novels making up the WWW trilogy of Wake, Watch, and Wonder have a very positive portrayal of artificial intelligence – and I wrote those precisely because very few other writers were portraying positive win-win outcomes from the advent of AI. I honestly don't know which scenario is more likely – that AI will be our downfall, or that it will be our savior. I *do* know that we will have only a very short amount of time from the first advent of AI to when we will no longer be able to do anything about it. That’s why science fiction is important: it’s the place where we work out the possibilities before they are realities, so we can respond nimbly when one of those possibilities actually comes to pass.

3. In Factoring Humanity, you discuss memory. Does any new discovery of memory interest/surprise you and change the way you see it?

Factoring Humanity dealt, in part, with false memories – and the thing I’ve become more conscious of in the intervening years is just how false almost all memories are. Of course, so much of our daily lives are recorded now – things we used to say in passing on the street or on the phone are now permanently recorded as text messages or emails, and so we can go back and look at them. The notion behind Factoring Humanity was that there is an objective truth against which memory can be checked; in the fifteen years since the book came out, with the advent of life-logging, digital recording, social media, and so on, that has very much our day-to-day reality.

4. Why are you so interested in memory?

Memory interests me because it’s almost never discussed when talking about who we are. We say our genes make us behave a certain way, or some unremembered part of our upbringing does. But, in fact, almost all of our behavior on a daily basis is the direct result of memory: do we look forward to going to work, or dread it? Depends on our memories of our job. When we see someone, are we happy or angry? Depends on our memories of our last encounter. Would we rather have Korean food or Italian food for lunch? That, too, depends on memory. It’s the single most potent defining force in who we are, and yet it’s almost never examined *as* a force. Factoring Humanity tackles the fundamental nature of memory.

5. It seems that you are excited about the technology that can let people go into each other’s memory. Do you also consider the possible negatives of this kind of tech or are you really optimistic about it?

Sure, I think about the downsides. But science fiction is a dialog: I explore one aspect of a problem; another author explores a different aspect. I don't have to stress every aspect in every story. I do value my personal privacy – because we have a society, currently, that looks to tear down other people, constantly hunting for any reason to discard another human being: Oh, twenty years ago he said this? Ten years ago, he did that? It’s become open hunting season on our fellow humans: the goal of many is to find the one slip-up, one peccadillo, the one off-hand comment that can be used as an excuse to gang up on, tear down, and throw out another person – reduce a lifetime of decades down to a few moments, judge those moments, and feel smug about having now shown the person to be less-than-perfect. Well, it’s an uncomfortable society to live in – and so I explore alternatives, including ones where there’s way more transparency, way more day-to-day accountability (focusing on what people are doing now, not what dirt we can dig up about them from decades ago), and way more empathy. To me, such societies would be better than ours currently is.

6. How did you first get into writing?

Like so many people, I was lucky enough to have some very encouraging teachers in school. As it happened, I had the same teacher for fifth grade and sixth grade, although she got married over the summer, so in the first of those she was Miss Matthews and in the second she was Mrs. Jones; I was precocious to enough to know that her first name was Patricia. This was the late 1960s, and there was no such thing as a school photocopier or a home computer, so I was writing stories by hand on foolscap. She loved my stories and had me copy out duplicates of them by hand so she could keep a copy, too. If she’s held onto them, she might get something for them on eBay today.

Starting in my teenage years, I got serious about wanting to be a writer. I submitted my first short story to a magazine in August 1976, when I was sixteen years old. It took three more years before actually sold something, in January 1980, when I was nineteen. The Strasenburgh Planetarium in Rochester, New York, had a science fiction short story writing contest judged by Isaac Asimov; I was one of the winners. It was only eighty-five American dollars, but it might as well been a million: I knew this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

7. Where is your favorite place for writing? Do you have any special writing rituals?

My living room! I have a nice recliner chair, a cordless ergonomic keyboard, two big monitors, a fireplace, and great views out of my penthouse windows. I love it. The only ritual is to get in the chair and start writing!

8. What was your most memorable novel to write?

Each one is certainly a unique experience. That said, in an odd way, my 1998 novel Illegal Alien was the most memorable because I wrote it so quickly; it just came pouring out through my fingertips after I’d finished my research. That novel was a courtroom drama with an extraterrestrial defendant, and once I was fully versed in trying homicide cases it was absolutely clear to me how to tell that tale and I got it done very quickly.

9. Are there any literary heroes you would cite as having a major influence on your writing?

Arthur C. Clarke taught me the sense of wonder and that you can write about metaphysical issues without being irrational. Isaac Asimov taught me that you can write exciting books without violence or physical action. H.G. Wells taught me to use science fiction as a means for social comment. Frederik Pohl taught me that characters don’t have to be likable but merely realistic. And Canadian writers Terence M. Green and Eric Wright taught me to keenly observe the minutiae of everyday life and the foibles of individuals.

Goodreads ** Amazon ** Barnes&Noble ** Kobo

About the author:

Robert J. Sawyer — called "the dean of Canadian science fiction" by The Ottawa Citizen and "just about the best science-fiction writer out there these days" by The Denver Rocky Mountain News — is one of only eight writers in history (and the only Canadian) to win all three of the science-fiction field's top honors for best novel of the year:

• the World Science Fiction Society's Hugo Award, which he won in 2003 for his novel Hominids;

• the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America's Nebula Award, which he won in 1996 for his novel The Terminal Experiment;

• and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, which he won in 2006 for his novel Mindscan.

According to the US trade journal Locus, Rob is the #1 all-time worldwide leader in number of award wins as a science fiction or fantasy novelist. Recent honors include the first-ever Humanism in the Arts Award from Humanist Canada, the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal from the Governor General of Canada, the Hal Clement Award for Best Young Adult Novel of the Year (for Watch), and a Lifetime Achievement Aurora Award from the Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Association — the first such award given to an author in thirty years, and only the fourth such ever bestowed.

The 2009-2010 ABC TV series FlashForward was based on his novel of the same name, and Rob was a scriptwriter for that series.

Maclean's: Canada's Weekly Newsmagazine says, "By any reckoning, Sawyer is among the most successful Canadian authors ever," and The New York Times calls him "a writer of boundless confidence and bold scientific extrapolation." The Canadian publishing trade journal Quill & Quire named Rob one of "the thirty most influential, innovative, and just plain powerful people in Canadian publishing" (the only other authors making the list were Margaret Atwood and Douglas Coupland).

Rob's novels are top-ten national mainstream bestsellers in Canada, appearing on the Globe and Mail and Maclean'sbestsellers' lists, and they've hit #1 on the science-fiction bestsellers' lists published by Locus, Amazon.com, Amazon.ca, Amazon.co.uk, and Audible.com. His twenty-three novels include Red Planet Blues, Triggers, Calculating God, and the "WWW" trilogy of Wake, Watch, and Wonder, each volume of which separately won the Aurora Award — Canada's top honor in science fiction — for Best Novel of the Year.

Rob — who holds honorary doctorates from the University of Winnipeg and Laurentian University — has taught writing at the University of Toronto, Ryerson University, Humber College, and The Banff Centre. He has been Writer-in-Residence at the Richmond Hill (Ontario) Public Library, the Kitchener (Ontario) Public Library, the Toronto Public Library's Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy, Berton House in Dawson City, the Canadian Light Sourcesynchrotron, and the Odyssey Workshop.

Rob has given talks at hundreds of venues including the Library of Congress and the National Library of Canada, and beenkeynote speaker at dozens of events in places as diverse as Los Angeles, Boston, Tokyo, Beijing, and Barcelona. He was born in Ottawa in 1960, and now lives just west of Toronto.

Author's Giveaway

a Rafflecopter giveaway

I was just wondering what the author has planned next?

ReplyDeleteI was wondering how the author comes up with the ideas for this book and others?

ReplyDeleteI was just wondering what is the author's favorite book?

ReplyDeleteI was wondering if the author writes in different genres or just concentrates on the one?

ReplyDeleteI was wondering what the author's writing process/routine was like?

ReplyDeleteIf your book was made into a movie who would star in it?

ReplyDeleteLast day! wishing you luck and success in your career!

ReplyDeleteI think that memory is a great concept to write about. Someone's perceptions versus what can be proven raises some interesting questions. For example, there is a debate going on today, in the news, about whether or not a man who is rapidly losing his mental faculties should be charged with a crime he can't remember committing.

ReplyDelete