"From its gritty dark beginning to climatic ending, The Outsider is an action packed and fast paced gripping tale that follows Supreme Court messenger turned law clerk Grayson Hernandez as he tries to help the FBI uncover the identity of the Supreme Court serial killer who strikes on the fifth of every month." - Kathleen, Goodreads

“THE OUTSIDER is as authentic and suspenseful as any John Grisham novel—and I like Grisham a lot.”—JAMES PATTERSON

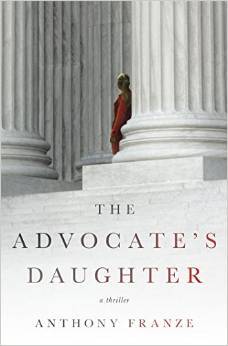

A young law clerk finds himself caught in the crosshairs of a serial killer in this breathtaking thriller set in the high-pressure world of the Supreme Court, from renowned lawyer Anthony Franze.

Things aren’t going well for Grayson Hernandez. He just graduated from a fourth-tier law school, he’s drowning in student debt, and the only job he can find is as a messenger. The position stings the most because it’s at the Supreme Court, where Gray is forced to watch the best and the brightest―the elite group of lawyers who serve as the justices’ law clerks—from the outside.

When Gray intervenes in a violent mugging, he lands in the good graces of the victim: the Chief Justice of the United States. Gray soon finds himself the newest—and unlikeliest—law clerk at the Supreme Court. It’s another world: highbrow debates over justice and the law in the inner sanctum of the nation’s highest court; upscale dinners with his new friends; attention from Lauren Hart, the brilliant and beautiful co-clerk he can’t stop thinking about.

But just as Gray begins to adapt to his new life, the FBI approaches him with unsettling news. The Feds think there’s a killer connected to the Supreme Court. And they want Gray to be their eyes and ears inside One First Street. Little does Gray know that the FBI will soon set its sights on him.

Racing against the clock in a world cloaked in secrecy, Gray must uncover the truth before the murderer strikes again in this thrilling high-stakes story of power and revenge by Washington, D.C. lawyer-turned-author Anthony Franze.

EXCERPT

PROLOGUE

When her computer pinged, Amanda Hill ignored it. This late at night, she shouldn’t have, but she did.

All her energy was focused on tomorrow’s closing argument. Her office was dark, save the sharp cone of light from the desk lamp. She’d waited for everyone to leave so she could run through her final words to the jury. So she could practice as she’d done a thousand times, pacing her office in front of imaginary jurors, explaining away the evidence against the latest criminal mastermind she’d been appointed to represent. This one had left prints and DNA, and vivid images of the robbery had been captured by surveillance cameras.

She glanced out her window into the night. Normal people were home tucking in their children, watching a little TV before hitting the sack. Her little girl deserved better. She should call to check in, but she needed to get the closing done. Amanda’s mother was watching Isabelle, and her mom would call if she needed anything.

There was another ping. Then another. Irritated, Amanda reached for the mouse and clicked to her email. The subject line grabbed her attention:

URGENT MESSAGE ABOUT YOUR MOTHER AND ISABELLE!

Amanda opened the email. Strange, there was no name in the sender field. And the message had only a link. Was this one of those phishing scams?

She almost deleted it, but the subject line caught her eye again. Her seven year old’s name.

Her cursor hovered over the link— then she clicked. A video appeared on the screen. The footage was shaky, filmed on a smartphone. The scene was dark, but for a flashlight beam hitting a dirty floor. Then a whisper: “You have thirty minutes to get here or they die.”

A chill slithered down Amanda’s back. This was a joke, right? A sick joke? She moved the mouse to shut down the video, but the flashlight ray crawled up a grimy wall and stopped on two figures. Amanda’s heart jumped into her throat. It was her mother and Isabelle. Bound, gagged, weeping.

“Dupont Underground,” the voice hissed. “Thirty minutes. If you call the police, we’ll know. And they’ll die.”

The camera zoomed in on Isabelle’s tear-streaked face. Amanda’s computer began buzzing and flashing, consumed by a tornado virus.

Amanda drove erratically from her downtown office to Dupont Circle. She kept one eye on the road, the other on her smartphone that guided her to the only address she could find for “Dupont Underground,” the abandoned street trolley line that ran under Washington, D.C.

Her mind raced. Why was this happening? It didn’t make sense. It couldn’t be a kidnapping for ransom. She had no money— she was a public defender, for Christ’s sake. A disgruntled client? No, this was too well organized. Too sophisticated. Common criminals, Amanda knew from her years representing them, were uneducated bumblers, not the type to plan out anything in their lives, much less something like this.

She checked the phone. She had only fifteen minutes. The GPS said she’d be there in five. She tried to calm herself, control her breathing. She should call the police. But the warning played in her head: We’ll know. And they’ll die.

She pulled over on New Hampshire Avenue. The GPS said this was the place, but she saw no entrance to any underground. It was a business district. Law firms and lobby shops locked up for the night. She looked around, panicked and confused. There was nothing but a patch of construction across the street. Work on a manhole or sewer line. Or trolley entrance. Amanda leapt from her car and ran to the construction area. A four-foot-tall rectangular plywood structure jutted up from the sidewalk. It had a door on top, like a storm cellar. The padlock latch had been pried open, the wood splintered. Amanda swung open the door and peered down into the gloom.

She shouldn’t go down there. But she heard a noise. A muffled scream? Amanda pointed her phone’s flashlight into the chasm. A metal ladder disappeared into the darkness. She steeled herself, then climbed into the opening, the only light the weak bulb on her phone. When she reached the bottom, she stood quietly, looking down the long tunnel, listening. She heard the noise again and began running toward it.

That’s when she heard the footsteps behind her. She ran faster, her breaths coming in rasps, the footfalls from behind keeping pace. She wanted to turn and fight. She was a god-damned fighter. “Amanda Hill, The Bitch of Fifth Street,” she’d heard the defendants call her around the courthouse. But the image of Isabelle and her mother’s faces, their desperation, drew her on.

The footsteps grew closer. She needed to suppress the fear, to find her family.

The blow to the head came without warning and slammed her to the ground. There was the sound of a boot stomping on plastic and the flashlight on her phone went out. The figure grabbed a fistful of her hair and dragged her to a small room off the tunnel. She was gasping for air now.

A lantern clicked on. Amanda heard the scurrying of tiny feet. She saw the two masses in the shadows and felt violently ill: her mother and Isabelle. Soiled rags stuffed in their mouths, hands and feet bound. Next to them the silhouette of someone spray-painting on the wall.

Amanda sat up quickly, and a piercing pain shot through her skull. She averted her eyes, hoping it was all a nightmare. But a voice cut through the whimpering of her family.

“Look at them!” Amanda lifted her gaze. She forced a smile, feigned a look of optimism, then mouthed a message to her daughter: It’s okay. Everything’s going to be okay.

It was a lie, of course. A godforsaken lie.

CHAPTER 1

Grayson Hernandez walked up to the lectern in the well of the U.S. Supreme Court. He wasn’t intimidated by the marble columns that encased the room or the elevated mahogany bench where The Nine had been known to skewer even the most experienced advocates. He calmly pulled the lever on the side of the lectern to adjust its height, a move he’d learned watching the assistant solicitor generals showing off. He stood up straight and didn’t look down at any notes; the best lawyers didn’t use notes. And he began his oral argument.

“Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the court—” He was immediately interrupted, not uncommon since the justices on average asked more than one hundred questions in the half hour of oral argument allotted to each side. But the voice, which rang though the chamber, wasn’t from a justice of the highest court in the land.

“I’ve told you before, Gray, you can’t be in here.” The beam of a flashlight cut across the empty courtroom. Gray held up a hand to shield his eyes. He smiled at the Supreme Court Police officer making his nightly rounds.

“Someday, counselor,” the officer said. “But for now you might wanna focus on getting the nightlies delivered.” The officer swung the ray of light to Gray’s messenger cart filled with the evening’s mail.

Gray waved at the officer, and returned to his cart. The wheel squeaked as he rolled it out of the courtroom and into the marble hallway.

In Chief Justice Douglas’s chambers, two law clerks were sitting in the reception area, fifteen feet apart, tossing a football between them. They seemed punchy, wired after a long day at the office, talking about one of the court’s cases.

“A high school has no right to punish a kid for things he says off school grounds. The court needs to finally say so,” one of the clerks said. He was a stocky blond guy. Gray thought his name was Mike. Mike spiraled the ball to the other clerk who looked kind of like a young JFK.

“You’re high if you think the chief is going to side with the student,” JFK said, catching the ball with a loud snap. “You upload a violent rap song on YouTube saying your math teacher is sexually harassing students, you’re gonna get suspended.”

“Even if it’s true?” Mike said. The Supreme Court had thirty-six law clerks, four per justice. It was an internship like no other, promising young lawyers not only a ticket to any legal job in the country, but also the chance to leave their fingerprints on the most important legal questions of the day. The current clerks were all in their late twenties, the same age as Gray, but that’s where the similarities ended. Like the two throwing the ball, almost all were white, from affluent backgrounds. Gray didn’t think there were any Mexican Americans in the clerk pool, and certainly none who grew up in gritty Hamilton Heights, D.C. They’d all gone to Harvard or Yale or institutions that, unlike Gray’s law school, had ivy instead of graffiti on their walls. And they certainly weren’t delivering mail.

Gray nodded hello as he lifted the stacks of certiorari petitions out of his cart and dropped them in the metal in-boxes for the chief ’s clerks.

Mike looked at Gray. “No, not more petitions, I’m begging you.” Gray smiled, but didn’t engage. His boss in the marshal’s office had a rule when it came to the justices and their law clerks: Speak only when necessary.

The ball whizzed across the reception area again. “Is it printed yet?” JFK asked. “I wanna get out of here.” He looked over to the printer, which was humming and spitting out paper. Gray worked tw night shifts a week, and there usually were no less than a dozen clerks still in the office. Theirs was a one-year gig, but they worked as if the justices wanted to squeeze five years out of them.

“It won’t take long,” Mike said. “It’s a short memo, and I just want someone who’s a disagreeable ass to point out any soft spots before I turn it into the chief.”

“You’re wasting your time. He’s never gonna side with the student, he—”

“This case is no different than Tinker v. Des Moines Schools,” Mike countered. “The court said disruptive speech at school could be punished, but not speech made off school grounds. Off-campus speech, including posting something on YouTube, should be covered by the First Amendment just like everything else. It’s none of the school’s business.”

JFK gave a dismissive grunt. “A rap expert from Greenwich, Connecticut, I love it.”

Mike threw the ball hard at his co-clerk. “Hey,” JFK said, shaking off the sting after reeling in the throw. “I’m just saying, the Tinker case was decided in the late sixties. You can’t apply it in the digital world. You’re in an ivory tower if you think the chief will blindly follow Tinker.”

Gray pretended not to listen, but he lingered, enjoying the intellectual banter.

The ball flew by again. “Ivory tower?” Mike said. “Fine, let’s ask an everyman.” He pointed the football at Gray. “Hey, Greg, can we ask you something?”

Mike had once asked Gray his name, a regular man of the people.

“It’s Gray.”

“Sorry. Gray. We have a question: Do you think if a high school student is off campus and posts something offensive on social media a school can punish him for it?”

JFK chimed in: “It’s not just posting something offensive. It’s a profanity-laden rap that accuses a teacher of sexually harassing students and threatens to ‘put a cap’ in the guy.”

Gray pondered the question as he retrieved mail from the outboxes. “I agree with what Murderous Malcolm said about the case.” The clerks shot each other a look. That morning the New York Times ran a story about the case, in which a famous rapper was interviewed and defended the student’s right to free speech. Every morning the Supreme Court’s library sent around an email aggregating news stories relating to the court. Gray was probably the only person at One First Street who read them all.

Gray continued. “I think the First Amendment allows a kid who saw a wrong happening to write a poem about it over a beat.” Gray wheeled the cart toward the door. “And if the chief justice disagrees, you might mention all the violence in those operas he loves so much.”

“That’s what I’m talking about,” Mike said, spiking the ball, then doing a ridiculous touchdown dance. He strutted over to Gray and gave him a high five.

For a moment, it felt like Gray was a clerk himself, an equal weighing in on the most important school-speech case in decades.

“Hey, Gray,” JFK said. Gray turned, ready to continue his defense of the First Amendment.

“I’ve got some books that need to be delivered to the library.”

When Gray arrived at the gym two hours later, his dad already had his hands wrapped and was hitting the heavy bag. There was a large sweat stain on his shirt. “You’re late,” he called out.

“I told you, I have the night shift on Sundays,” Gray said. His dad didn’t respond, just pounded the bag. He wasn’t going to get any sympathy from Manny Hernandez about the night shift. This was his father’s one night off from the pizza shop. Since his dad’s cancer went into remission, they’d been meeting every Sunday night at the old boxing club in Adams Morgan. Gray would have preferred that they spent these times together somewhere other than a smelly gym, but it made his father happy to see him back in the gloves. It was these moments that Gray was reminded that he probably wasn’t the man his father had dreamed he’d become. With his books and big dreams, Gray was his mother’s boy.

Gray punched the bag, the hits vibrating through him, his thoughts venturing to his earlier encounter with the law clerks. He threw his weight into his right.

Let’s ask an everyman.

Then his left.

I’ve got some books that need to be delivered to the library.

Gray continued to pummel the bag, his heart pounding, sweat dripping from his brow.

“Somethin’ wrong?” His father came and stood behind the bag, holding it in place as Gray kept going at it. “Talk to me.”

“It’s nothing,” Gray finally said, catching his breath, wiping his forehead with his arm. “Just work stuff.”

“I thought it was going well. You’ve loved that building since you were a little kid. And now you’re working there, helping the justices.”

“I don’t think delivering the mail is exactly helping the justices, Dad.”

“It’s a foot in the door. Once they get to know you, see how smart you are . . .”

Things didn’t work that way, but Gray wasn’t in the mood to argue.

“It’ll happen, son,” his father added. “You just gotta pay your dues, Grayson.”

“I know, Dad, I know.”

CHAPTER 2

At seven the next morning, Gray sat at his cubicle, tired and his muscles aching from the workout the night before. He started his day, as always, slugging down a large coffee while reading SCOTUSblog, a website that covered the court. It was the first day of the new term, and the pundits predicted it would be an exciting year with several landmark cases.

Gray turned when he felt a hand on his shoulder. Shelby, one of the marshal’s aides. A mistake he’d made after a night of drinking with the other aides. She made a point of saying she’d never been with “a guy like him,” which he assumed meant a poor kid from a sketchy side of D.C. She worked part-time while finishing her senior year at Georgetown.

“Martin wants to see you,” she said. Gray looked across the expansive cube farm. He could see Martin Melnick, their supervisor, through the glass walls of his small interior office in the back. He was eating something wrapped in foil. A breakfast burrito, maybe. Shelby’s expression summed up her assessment of Martin: Ick. Martin was in his late thirties, ancient by aide-pool standards. Overweight with bad teeth, he was the antithesis of the bright young things who worked at the high court, the butt of many jokes. He was never particularly nice to Gray; the opposite, actually. But Martin was good at his job and didn’t deserve the ridicule, so Gray kind of rooted for him in all of his slobbiness. Before Gray made his way over to Martin, Shelby said, “Who’s that?” She pointed to a photo pinned to Gray’s cubicle. It was of a boxer in the ring, bruised and battered, arms in the air, standing over his opponent who was out cold.

“My dad, back in the day. He was a fighter in Mexico.” Gray had pinned it up his first day on the job. His own Facebook motivational meme.

Shelby squeezed Gray’s bicep. “I see where you get—”

“I’ve gotta get over to Martin,” Gray said, politely extracting himself.

Martin’s office didn’t help his image. Stacks of papers everywhere. Post-it notes all over the place. He glanced up at Gray and handed him an envelope.

“We got a rush delivery for E.R.D.’s chambers.” E.R.D. were the initials for Edgar R. Douglas, the chief justice. In his month on the job, Gray had learned that the Supreme Court was obsessed with abbreviations and acronyms.

“Oral arguments start at ten, so get this to his clerk ASAP. His name’s on the envelope.”

Gray fast-walked up to the main floor, shuttling through the impressive Great Hall that was lined with marble columns and busts of past chief justices. He nodded at the officer manning the bronze latticework door and made his way to the chief justice’s chambers. The chief ’s secretary, a tough old bird named Olga Romanov, flicked him a glance.

“I have a delivery for Keir Landon.” “The clerks are getting breakfast,” she said in her clipped Eastern European accent.

“Do you know where?”

“Breakfast. Where do you think?” Gray forced a smile, then headed back downstairs to the court’s cafeteria. He marched past the assembly line of trays and the public seating area and into the private room reserved for the law clerks. A group of four were sitting at the long table.

Gray cleared his throat when they didn’t look up. When that didn’t work: “Excuse me. I have a delivery for Keir Landon.”

The guy from last night who looked like JFK popped his head up. He walked over to Gray and plucked the envelope from his hand.

“What’s up, Greg?” Mike said from the group. Before Gray could correct him again on the name, Gray’s phone pinged. A text from Martin, another rush delivery.

Gray hurried out, tapping a text to Martin as he paced quickly through the cafeteria. He didn’t look up until he bumped into someone. A tiny woman in her seventies. It was only when the elderly woman’s food tray hit the floor that Gray recognized her: Justice Rose Fitzgerald Yorke. She looked different without the black robe. Always weird seeing the teacher out of school. Yorke was one of the most beloved members of the court. Gray had read that when Yorke graduated from Harvard in the fifties, the only woman and number one in her class, none of the white-shoe law firms would hire a woman as a lawyer. A few had offered to make her a secretary. Maybe that explained why she ate in the public cafeteria rather than the justices’ private dining room, or why she organized the office birthday celebrations for every single employee at the court. She knew what it was like to be an outsider. She brought what some would derisively call empathy to her jurisprudence.

Justice Yorke bent over to pick up her spilled plate and silverware.

“Justice Yorke, I’m so sorry. Please, let me clean this up.” Gray lightly put a hand on the elderly justice’s arm.

“It’s no problem, young man, I can clean up after myself.”

“No, really, it’s my fault. Please.”

The manager of the cafeteria was standing there now looking annoyed. He gestured for Justice Yorke to come with him to get a new plate. The manager shot Gray a hard look as he spirited the justice away.

So there he was on the first Monday in October— the opening day of the term—on hands and knees wiping up the floor, the clerks passing by on their way back to chambers.

You just gotta pay your dues, Grayson.

CHAPTER 3

At the end of his shift, Gray headed down to the court’s garage to get his bike. In the elevator down, he contemplated his dinner options. He wasn’t sure if he could take another night of ramen or SpaghettiOs. Maybe he’d go to the pizza shop. Or to his parents’ apartment. Mom could always be counted on for a good meal, and he could bring some laundry. The elevator doors spread open to a field of gray concrete. The bike rack was empty but for his beat-up Schwinn. As he unlocked the chain, he heard a commotion. In the back, behind one of the support beams.

Gray stepped toward the sound. Next to an SUV parked in a reserved spot he saw two men, one had fallen on the ground, the other standing over him. The guy must have slipped. Was he hurt? There was something about how he didn’t try to get up and the stance of the other man that didn’t seem quite right.

“Everything okay?” Gray said. The man who was standing whirled his head around. That’s when Gray noticed the ski mask.

Before Gray could process the situation, the assailant had kicked the man on the ground and charged Gray.

Gray’s father had taught him that when someone is coming at you, in the boxing ring or on the street, time slows. Nature’s way to give you a chance to evade the predator. And that was how Gray dodged the blade that lashed in a wide arc, grazing his abdomen. A panic washed over Gray. And when the attacker came at him again, it wasn’t one of Dad’s bob-and-weaves that saved him, but a crude kick— more Jason Statham than Cassius Clay— that connected to Ski Mask’s chest. The guy slammed into a car, but he didn’t go down. He roared forward at Gray again. Gray did a bull-fighter’s move and pushed the attacker past him, but felt a bite in his side. Ski Mask then jammed something into the small of Gray’s back. He felt a jolt of electricity burning into him— a shockwave up his spine— causing him to spasm and gasp for air. Gray went black for a moment, and then was flat on the cold concrete.

Gray watched as Ski Mask turned his attention to the other man who was on his feet now. It was only then that Gray got a good look at the victim: Chief Justice Douglas. The chief had scurried behind a car and was frantically thumbing a key fob, his panic button. The elevator dinged and Gray heard the slap of dress shoes on concrete, the court’s police.

Still on the ground, Gray shifted his eyes toward the man in the ski mask, but he was gone. Gray’s vision blurred. He heard yelling. Then things went dark.

CHAPTER 4

Gray awoke to the scent of disinfectant and the presence of a crowd in the small hospital room. He must’ve been given painkillers because it was like watching a sitcom, one of those Latino family comedies written by white guys from Harvard. There was Mom, hovering over him, wiping his brow, pushing the giant plastic jug of hospital water at him. Dad, looking tired and too thin, wearing a flour-stained apron, staring at the old box television mounted from the ceiling. And big sis, Miranda, wrangling Gray’s seven-year-old nephew, Emilio.

When they noticed his eyes open, they called for a doctor, and soon an intern was checking Gray’s pupils with a penlight.

Gray never got into drugs, but as he sat back in the relaxed haze, he was starting to understand the fascination. And for the next hour, or maybe it was longer, his family kept talking to him— asking about the garage attack— and he gave woozy responses. God knows what he said.

Sometime later, Gray’s attention turned to a familiar voice at the doorway.

“Always gotta be the hero.” One of his oldest friends, Samantha. When they were in elementary school, Gray had intervened to save Sam from a schoolyard bully, only to have the kid then pummel Gray until Sam put an end to it by giving the kid the worst wedgie Gray had ever seen. Sam still gave him shit for it.

As Sam hugged everyone hello, Gray’s father shadowboxed and said, “He used the moves I taught him.”

Gray didn’t have the heart to tell him that most of the credit went to Jason Statham.

Sam came to his bedside and punched him in the arm.

“What was that for?”

“For being so stupid. You’re lucky to be alive.”

“That’s what I said to him,” Mom said. The room grew loud again with his family talking over one another. Gray watched as his nephew reenacted Gray’s confrontation with the mugger. He was feeling the pull of sleep, more drugs they’d put in the IV, and closed his eyes. He was just about to drift off when the room went suddenly quiet, a rarity at any Hernandez gathering.

His eyes popped open at another voice. “I owe you a thank you.”

There was a tall man standing at his bedside. He wore a sports jacket, shirt open at the collar. It took Gray a moment to realize it wasn’t the drugs, it was really him. Chief Justice Douglas. “It was nothing,” was all Gray managed in response. “No, if you hadn’t arrived when you did, then . . .” the chief’s voice trailed off.

Gray introduced the chief justice to his family. He noticed the chief hold Sam’s gaze a beat longer than comfortable when they shook hands. Sam had that effect on men, and Gray supposed Supreme Court justices were not immune to her beauty. To Gray, she was still the flat-chested tomboy he used to play dodgeball and video games with.

After the introductions, the chief pulled up a chair next to Gray’s bed. It was awkward to talk because the room was compact and his family wasn’t too subtle about the gawking.

“Someone at the court told me you’re a lawyer?” the chief said.

“Top of his class,” Gray’s mother said.

“Mom, please.” Gray felt his face flush.

The chief justice smiled. “The doctors said you’ll be out of commission for a few days.”

“That’s what they said, but I don’t think it’ll be more than a day. I’m already feeling—” He stopped when he saw the hard look his mother was giving him.

“It’s always wise to listen to your mother,” the chief said with a dry chuckle.

His mom nodded, giving a satisfied smile.

“But do me a favor, would you?” the chief continued.

“Of course.”

“When you get back to work, come by my chambers.” Before Gray could respond, the chief added, “You’re not gonna be a messenger boy anymore.”

CHAPTER 5

“Nothing? They found nothing?”

Special Agent Emma Milstein asked. Her partner, Scott Cartwright, stood in front of Milstein’s desk in the FBI field office, staring into an open file. Cartwright wore his usual navy suit, white shirt, plain tie clamped around his thick neck.

Cartwright shook his head. “A guy with a knife strolls into the Supreme Court, attacks a justice, and not one camera catches him, no one knows how he got in or out, nothing?”

“Nada,” Cartwright said.

“What about the kid? What’s his name again?” Cartwright flipped a page in the file.

“Hernandez. Grayson Hernandez. The Supreme Court’s squad interviewed him. Been on the job there for about a month, well liked. They’re confident it was just wrong place, wrong time.”

“Criminal record?”

“No, he’s a lawyer, actually.”

“A lawyer? I thought he was a messenger?”

“Yeah, works in the marshal’s office. Times are tough in the law business, I guess,” Cartwright said.

“I guess so. Our guys agree with the Supreme Court’s police? We’re sure Hernandez is clean?”

Cartwright walked over and put the open file in front of Milstein. “We don’t think he was involved in the attack. He got into some trouble as a kid— joyriding in a stolen car with some friends. But that’s like jaywalking in Hamilton Heights.”

“He grew up in Hamilton Heights? Don’t they call that area ‘Afghanistan’?” Milstein looked down at the file, studying the photo of Grayson Hernandez. He was a good-looking kid. Late-twenties. Striking blue eyes, unusual for a Hispanic. He had a scar that ran from the corner of his left eye to his ear. Jagged, no plastic surgery. “Yeah, he’s a regular local boy makes good,” Cartwright said, heavy on the sarcasm.

“Any criminal associates?”

“He was childhood friends with a real charmer, Arturo Alvarez, who’s just out of prison and already at war with a rival sect. But it appears that Hernandez left the Heights and never looked back. The report says no contact with Alvarez in years.”

Milstein read through the rest of the file. “Does the press know he was there when the chief was attacked? I don’t need reporters sniffing around. If they find out there’s a connection to Dupont Underground they’ll—”

“They don’t know anything,” Cartwright interrupted. “The court released a statement about the mugging, but no details. They’re pretty tight-lipped up there.”

“What’s the Supreme Court’s police chief saying?”

“Aaron Dowell? He’s saying we should mind our own fucking business. They’re in charge of protecting the chief.”

“Yeah, they’re doing a great job.” Cartwright said nothing. “When can we talk to the chief justice?” Milstein asked. “They’re still stonewalling. I don’t think they’re taking the connection to Dupont seriously.”

“You told them we think it’s the same perp?”

“Of course I did. I’m working on it, Em.”

“Work harder.” Milstein let out a loud, frustrated breath.

“You want me to get you a snack or something?” Cartwright said. “When my kids get a little cranky, I bring them some Goldfish crackers and it—”

“Any luck on getting the wires?” Milstein said, ignoring him. Cartwright made a sound of disbelief. “Neal says you’re crazy if you think you’ll get a bug anywhere near that building.” As usual, Neal Wyatt, the assistant director in charge of the field office, was being too cautious, playing politics.

“Cowards.”

“You need to tread lightly. This is the Supreme Court.”

“The Franklin Theater fire was on July fifth. The Dupont Underground murders on August fifth. Now the attack on the chief October fifth. And we now know it’s the same perp. What’s it gonna take to get the Supreme Court’s squad to take this seriously?”

Cartwright shook his head. “Hopefully not another victim on November fifth.”

Goodreads ** Amazon ** Barnes&Noble

About the author:

ANTHONY FRANZE is a lawyer in the Appellate and Supreme Court practice of a prominent Washington, D.C. law firm, and a critically acclaimed thriller writer with novels set in the nation’s highest court. He is a board member and a Vice President of the International Thriller Writers organization.

No comments:

Post a Comment