Scotland Yard inspector Ian Rutledge returns shell shocked from the trenches of World War I, tormented by the memory of Hamish MacLeod, the young Scots soldier he executed on the battlefield. Now, Charles Todd features Hamish himself in this compelling, stand-alone short story.

Before the Great War, Hamish farms in the Highlands, living in a small croft on the hillside and caring for a flock of sheep he inherited from his grandmother. When at the height of a spring gale, he hears a faint cry echoing across the glen, Hamish sets out into the stormy night to find the source. Near the edge of the loch he spots a young boy lying wounded, a piper’s bag beside him. Hamish brings the piper to his home to stay the night and tends to his head wound, but by the time Hamish wakes the boy has vanished. Worried, he goes in pursuit of the injured piper and finds him again collapsed in the heather--dead.

Who was the mysterious piper, and who was seeking his death? As Hamish scours the countryside for answers, he finds that few of his neighbors are as honest as he, and that until he uncovers a motive, everyone, including Hamish, is a suspect.

GUEST POST

WHO IS HAMISH?

We’ve asked ourselves that many times. You’d think, after nineteen mysteries where he’s one of the main characters that we might have a clue by now.

We’ve asked ourselves that many times. You’d think, after nineteen mysteries where he’s one of the main characters that we might have a clue by now.

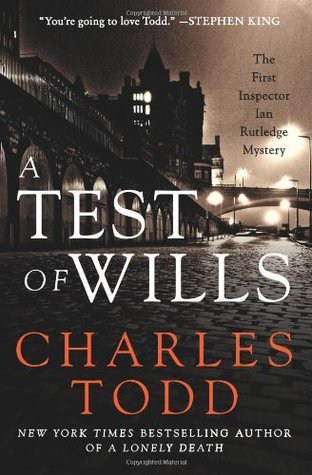

He made his appearance in the first Rutledge, A Test of Wills. But that wasn’t planned. We did know that Rutledge suffers from shell shock, which he tries to hide from those around him. Today we know it as PTSD, but in the Great War it was considered a sign of weakness, lack of moral fiber, a man who broke under fire. Hardly a description of Ian Rutledge, who was decorated several times for his acts of courage. He never asked his men to do something that he wouldn’t do as well, and they knew that. But the battle of the Somme in July, 1916, broke many men. And Corporal Hamish MacLeod was the first of Rutledge’s company who did. He refused to obey a direct order in the midst of a battle: he refused to ask exhausted men to try again to take the German machine gun nest they had been assigned to capture. They’d been trying since dawn, and their wounded and dying lay all around them. Hamish knew—Rutledge knew—that it was folly. But wars have to be fought by the rules, or there is mutiny and chaos. (The French were to face a mutiny the very next year.) Rutledge threatened Hamish with death—did everything he could think of to persuade him to change his mind. In the end, he had no choice but to execute the young Scot. And he had just delivered the coup de grâce as Hamish lay dying, when the British artillery dropped a shell on their own trenches, and Rutledge’s remaining company was killed after all.

Rutledge survived. Soldiers will tell you what survivor’s guilt means. You made it out alive when no one else did. Why? Why you, and not the man beside you or just in back of you? Why did you deserve to live?

Rutledge survived. Soldiers will tell you what survivor’s guilt means. You made it out alive when no one else did. Why? Why you, and not the man beside you or just in back of you? Why did you deserve to live?

He tried to forget Hamish, to put him out of his mind. Instead, rather than face the fact that he’d killed Hamish—that he hadn’t died in that shell blast—he keeps him alive in his head. He knows Hamish is actually dead, buried in France. He knows Hamish is not some ghost risen from the grave. And yet—and yet, this is a voice Rutledge sometimes answers aloud, it’s so real, so embedded in his mind that he’s afraid that if he turns too soon or glances over his shoulder he might actually see the man whose voice it is, standing there, accusing him. Impossible, he tells himself. But a part of him believes that shutting off the voice would be killing Hamish a second time, and he can’t bear that. Instead he tries to find a way to cope, to live with the one thing he fears most.

It’s a tragic situation, and one faced over and over again by soldiers from every war. You take a good man, most likely brought up in his church and told as part of his faith, Thou shall not kill. Then you train him to be a soldier, teach him to kill mercilessly because if he shows compassion, he’ll be the one to die, not his enemy. And you send him out into something as horrible as the trenches, where he sees Death in its most devastating form, and let him watch his friends die around him. It isn’t surprising that such images stay in the brain and haunt you. Suicide is one way out, and Rutledge has even considered that from time to time. Facing his guilt is another way out, and Rutledge tries hard to do just that, a constant and agonizing struggle.

So where did all this come from? We realized that Rutledge had survived the war without any grave wounds. Just as well, if he expects to return to the Yard! But he wouldn’t have been a believable character if he’d waltzed back into civilian life after four years in the trenches. He’d been a very good detective before the war—yet somehow we needed to show the reader how he had changed from the man he’d been in 1914.

So where did all this come from? We realized that Rutledge had survived the war without any grave wounds. Just as well, if he expects to return to the Yard! But he wouldn’t have been a believable character if he’d waltzed back into civilian life after four years in the trenches. He’d been a very good detective before the war—yet somehow we needed to show the reader how he had changed from the man he’d been in 1914.

We’d talked to psychologists who dealt with PTSD, we talked to veterans of several wars, and we read all we could find about shell shock. But somehow we didn’t put all that together. We were working on a scene in Rutledge’s very first case since the war. Rutledge was interviewing a shell shocked veteran who had witnessed a murder, a man who stayed drunk in the hope of escaping his memories and was almost impossible to get a coherent answer from. And a voice in Rutledge’s head said, “That will be you soon enough, you can’t escape descending into a man like that.” Or words to that effect. It was our turn to be shocked. We realized that we’d found our answer. In the early days of the war, Rutledge had been assigned to a Scots regiment. And so the voice would surely have a Scottish accent and a Scots name…

Hamish has been there throughout the books, but we’re still intrigued with him. In fact we wrote a number of mystery short stories where Hamish was alive and serving with Rutledge in the trenches. He’s an interesting man, very conservative in some ways, like many of the Highlanders of his day. He’s intelligent, he has a good mind for military matters, and Rutledge trusted his judgment, often stood watch with him in the dark hours before a dawn attack. In one of the books, Legacy of the Dead, Rutledge encounters the woman Hamish loved. “Yesterday,” in a short story collection (Original Sins), edited by Martin Edwards, we see Hamish and Rutledge meeting for the first time as the regiment sails for France.

And then Danielle, a friend and our favorite publicist, asked one day, “Why haven’t you ever done a short story where Hamish solves the mystery himself?” Hmmmm. “The Piper” was our answer. Have we fully understood Hamish yet? We doubt it. But in many ways, the better we understand Hamish, the better we understand Rutledge and why he was so shaken by what he’d done. Hamish also stands for so many young men Rutledge led into battle, watching them die or be torn apart by machine gun fire and artillery. Like many an officer, he can remember their faces, even though he barely had time to learn their names before they were killed. That was the nature of the Great War, and one of the reasons it makes such a fascinating backdrop for this series. The nuances, the possibilities, the interactions, the aftermath give the period a dramatic personality all its own. Later, Julian Fellowes was to use the war in much the same fashion, in Downton Abbey.

Hamish is part of Rutledge, part of his history, but he’s so much more. And we hope our readers have come to like and respect him as much as we do. As much as Rutledge did before the bloody battle of the Somme, and still does in spite of all that Hamish now represents.

Caroline and Charles Todd

Goodreads ** Amazon ** HarperCollins

About the author:

Charles Todd is the pen name used by a mother-and-son writing team, Caroline Todd and Charles Todd.

Writing together is a challenge, and both enjoy giving the other a hard time. The famous quote is that in revenge, Charles crashes Caroline’s computer, and Caroline crashes his parties. Will they survive to write more novels together? Stay tuned! Their father/husband is holding the bets

No comments:

Post a Comment